Revisiting childhood trauma in Diane Keaton's memory

We can now add "outliving Diane Keaton" to the list of grievous offenses Woody Allen has committed.

No further words need to be written about the cultural impact of The Godfather movies, or Annie Hall, or Keaton's influence on fashion and feminism. I was fascinated by her 21st-century career, when she played interchangeable neurotic rich white ladies in interchangeable comedies where the most pressing issue anyone has is whether to spend Christmas in New York City or Aspen. I took a stab at writing about them, but lost the will to continue after watching Town & Country, one of the worst movies I've ever seen, though Keaton wasn't worse than anyone else in it.

But they weren't all that terrible, and honestly, I can see why the blandly cheerful sameness of a Nancy Meyers movie was appealing. The lady just needed a break. Keaton's post-Annie Hall through the early 90s filmography consisted mostly of serious (if not downright depressing) features, including Interiors, Shoot the Moon, Reds, and The Little Drummer Girl. Most depressing of all was 1977's legendary downer Looking for Mr. Goodbar.

If you haven't seen Looking for Mr. Goodbar, it's okay. Up until last year, it hadn't been available on any medium since 1997. While it's now for rent on Amazon Prime and YouTube, your best bet is the very nice Vinegar Syndrome Blu-ray, with its original disco-heavy soundtrack intact. It very much lives up to its reputation as a bleak, lurid drama about a troubled woman's descent into the hellish New York City singles scene, one that burned itself into my brain after seeing it far too young.

I've written before about growing up with overly permissive parents who refused to monitor what I watched or read. A lot of Gen Xers have similar stories about parents who treated them like miniature adults, sending them to buy cigarettes, letting them sip from cans of beer, forcing them into secondary parent roles for their younger siblings. My parents took that a step further, putting virtually no restrictions on the media I consumed, and often talking to me like a peer. The latter became actively damaging by the time I was a teenager, but even when I was younger, it often felt like I was living with two much older siblings than parents, both overly permissive, not terribly interested in child-rearing, and desperate to be perceived as "cool."

On the upside, it was instrumental in my being a horror obsessive. I saw Halloween too young, then Salem's Lot not long after that, and while both scared me, it was an intriguing and fun kind of scared. I began seeking out ghost stories, and then more horror movies, and so began a near-lifelong love for the macabre. On the downside, I was exposed to things I had no business seeing at such a young age, like Looking for Mr. Goodbar.

I was five years old. Five. The film was released in October of 1977, which would have made me just starting kindergarten. I don't know what my parents were thinking, or why they didn't bother availing themselves of any of my grandparents' offers to babysit me. I don't know what the theater employee was thinking when they let a child into that theater, or what any of the people who sat around us must have thought. As for the movie itself, I'm sure I must have thought it was boring, just a bunch of adults talking and looking sad, and occasionally taking their clothes off. But that ending seared itself into the back of my eyes forever, and even if I had never revisited the film as an adult decades later, I would never forget it.

If you've never seen Looking for Mr. Goodbar, I'm about to spoil the ending: after a hook-up goes sour, protagonist Theresa Dunn is raped and murdered. I couldn't have known then what was happening to her, only that it was bad. Director Richard Brooks shot it like a strobe-lit nightmare, mercilessly drawn out, the closing shot Theresa's white, staring face looking directly at the viewer over the sound of her ragged, dying breaths. That image has haunted me for more than 40 years.

When I watched Goodbar again, I assumed the ending wouldn't be as upsetting as I remembered. I was certain I had conflated it with other similarly brutal scenes from the countless horror movies I've seen since then. Instead, it was even more upsetting, precisely because now I knew what was happening to Theresa. More importantly, I knew why it was happening. Men sometimes, too often, react to rejection with violence. It's a fact of being a woman: if you're lucky, you just get called a bitch or told that you're too ugly to rape. I also knew by then that Theresa staring at the viewer as she dies is a challenge, daring them to judge her, to think that she's deserved such a brutal punishment for the crime of doing what she wants.

If you haven't seen Goodbar yet, I'm probably not selling you on it. But it's an excellent film, and a fascinating companion with Saturday Night Fever, released the same year, both of them about wayward young Catholics chafing at the predetermined roles their families created for them and finding freedom in New York City nightlife. From a modern perspective, late 70s New York City nightlife looks grubby and dangerous, but that danger is also alluring and exciting. It's a bold move to confidently step into that sweaty, grimy world and spend time with people who demand nothing of you but your body.

Looking for Mr. Goodbar started as a novel by Judith Guest, based on the real-life 1973 murder of schoolteacher Roseann Quinn. As it would now, the media treated Quinn's murder as the inevitable outcome of her habit of picking up strangers for sex, and Quinn herself as a cautionary tale for other women who might be thinking about doing the same thing that men have been doing since time immemorial (casually getting their rocks off), rather than a whole person who had a life before becoming a crime statistic.

Theresa Dunn's taste for casual sex is but a small part of who she is, driven by the pressure of familial and societal expectations, body image issues, forever living in the shadow of her glamorous older sister (Tuesday Weld), and near-constant disappointment with the men in her life. She's a good girl who wants to be bad, but feels guilty about wanting to be bad, while resenting that guilt at the same time.

Salvation from her baser desires seems to come in the form of James (William Atherton), a classic nice guy who represents safety and security, but he pushes her towards marriage and kids, neither of which she wants. As a balance, she also sees Tony (Richard Gere), a hot idiot who doesn't want anything but an easy fuck, until he becomes possessive and abusive. Her father (Richard Kiley), the one man who should be a source of unconditional love, has nothing to offer but withering contempt for Theresa daring to live her own life. How is performing this miserable nothing is ever good enough juggling act better than just hooking up with strangers?

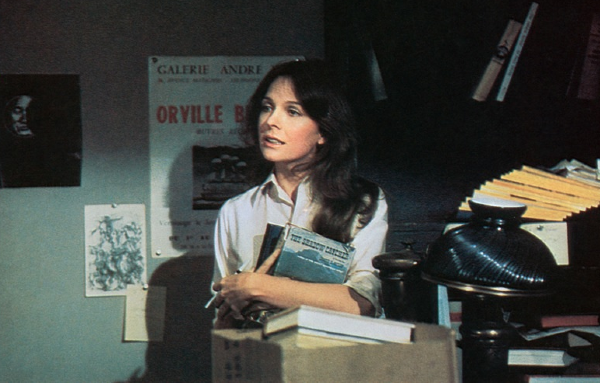

Though she won an Oscar for Annie Hall, released the same year, this is the better Diane Keaton performance. In fact, it's her greatest performance. Theresa has multiple personas: hard-edged party girl, dedicated teacher, meek daughter, budding feminist. Her lowest moment isn't when she's jumping into bed with a stranger, but when her piece of shit college professor-turned-lover casually dumps her, and she begs to know what she did wrong. The cynical "I've seen it all" face she puts on at the bars is to hide that shameful neediness, the desire for love that we all struggle with, in one way or another.

That ending is more harrowing than I remembered because Diane Keaton makes it harrowing. Frustration quickly turns to confusion, then terror, and it all feels very raw and real, and something we shouldn't be watching. Who can even imagine how hard it was to film that scene? Even Tom Berenger, who played Theresa's rapist/killer, noted that the experience gave him nightmares long after filming. No wonder she spent the last 30 years of her career in the plush comfort of movies that could have doubled for Crate and Barrel catalogs. She deserved it.

Comments ()